POP ART: THE POLITICAL REINVENTION THAT TURNED CONSUMPTION INTO CRITICISM

Pop Art was not a superficial trend, but an artistic and political revolution that used the icons of consumer society to question its own superficiality and numbing effect.

From its beginnings in the mid-1950s in Britain and its subsequent rise in the United States during the 1960s, Pop Art emerged as an artistic revolution that transcended mere frivolity to become a sociopolitical mirror of the consumer age. Contrary to the shallow perception that dismisses it as "easy art" for a "slow audience," this movement reveals itself as a profoundly aware visual expression of the reality that surrounded it.

CONSUMER CULTURE AS CANVAS

Pop Art arose as a direct response to Abstract Expressionism, which dominated the art scene at the time with its focus on emotion and the unconscious. Pop artists, by contrast, chose to document the immediate and everyday reality: a society defined by rapid consumption, technology, leisure, and trends. This art aimed to reunite life and art, but did so through a cold, direct, and rational aesthetic stripping the work of the intense emotional weight that had previously dominated.

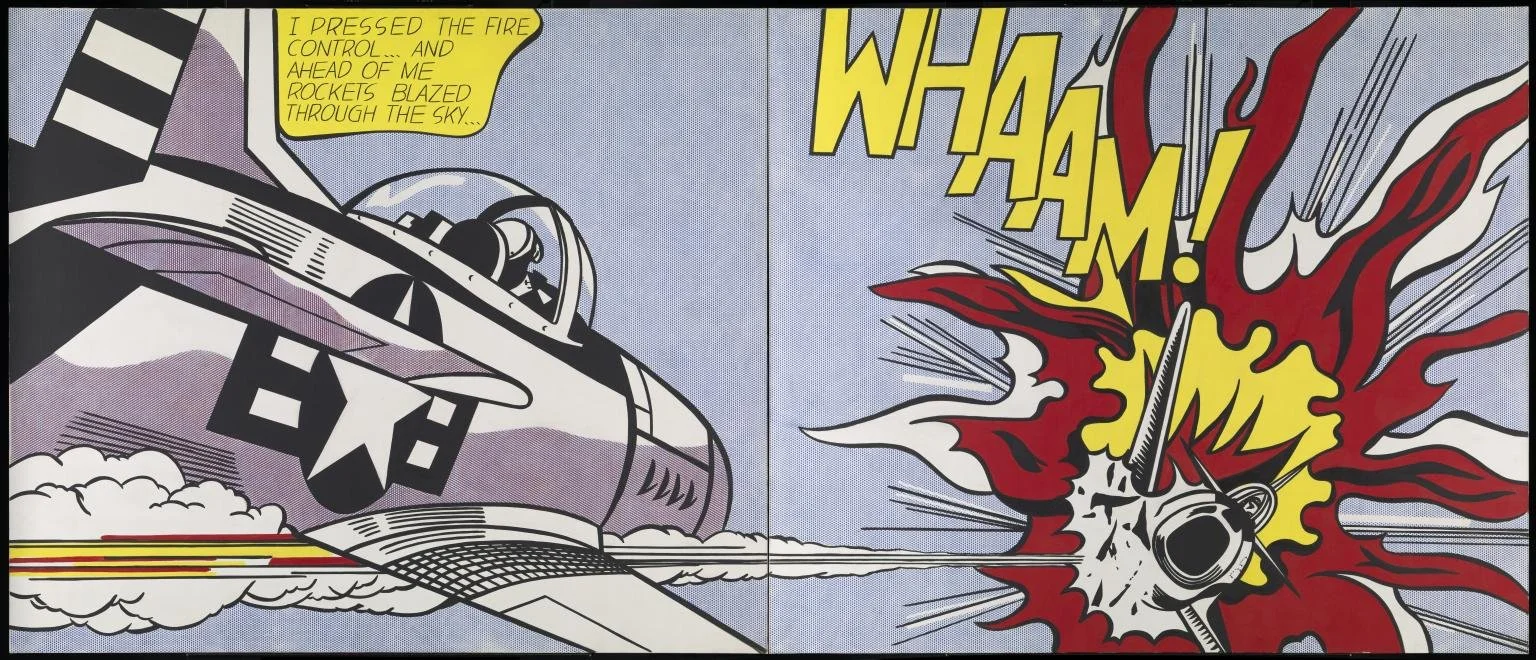

The raw material of Pop Art was not found in myths or introspection, but in the elements of the cultural industry: advertising, comic books, celebrities (the "saints" of the new faith), and the most banal objects of daily life, such as canned goods, bottles, and logos. For these artists, art had become just another producto capable of being mass-produced for higher output thus reflecting the standardized and mass nature of the culture they observed.

THE AESTHETICS OF REPETITION AND UNDERLYING CRITIQUE

The visual style of Pop Art is unmistakable and deliberately attention-grabbing, using bold, contrasting colors and relying on printing and silkscreen techniques. However, one of its most distinctive features is the repetition and seriality of images and objects. Iconic works such as Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans, featuring 32 nearly identical paintings, embody this spirit: they allude to mass-produced, packaged, and ready-to-consume godos repetitive and standardized.

This repetition is not just an aesthetic resource, but a critical act. It reflects and amplifies the superficiality, inexpressiveness, and impersonality of mass culture. It creates a “saturating effect” that, according to the artists, mimics the anesthetic effect of advertising and consumption in modern life lulling society into triviality so it forgets the serious problems looming over it. Pop Art, therefore, uses consumer culture’s own weapon its commercial and flashy aesthetic to hold up its most critical mirror.

Irony and social critique are, in fact, guiding threads throughout the movement. Although it celebrates popular culture, it simultaneously uses humor to question the values of consumer society. Pop Art is not "popular" in the sense of folklore or tradition, but adopts the term “pop” in its American sense linked to mass culture and consumer society. It sought to be a mirror in which postwar society could see itself. In a twist that redefines the relationship between art and the world, for Pop Art, “art no longer imitates life, but life imitates art.”

LEGACY AND CONTINUITY

Pop Art was a revolutionary movement that achieved international success, breaking down the traditional hierarchy between "high culture" and "popular culture" and challenging the idea that art must be transcendent or inaccessible. Its roots lie in movements like Dada, particularly in the work of Marcel Duchamp, who had already questioned the boundaries between high and low culture through the use of everyday objects.

Considered the first contemporary art movement, its legacy endures today. Its symbiotic relationship with advertising borrowing its elements to make statements, while inspiring it in return with its visual aesthetic and its ongoing influence on contemporary artists like Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, demonstrate that Pop Art was not a passing fad. It was, and still is, a deep and political analysis of a culture that finds in its icons and in its consumption a kind of religión one that saturates and, paradoxically, numbs.