MARILYN MONROE: HOLLYWOOD'S MOST ENIGMATIC WOMAN

Beyond the glamour, Marilyn Monroe was an unstoppable force. This brilliant mind dominated Hollywood, rewrote the rules of power and fame, and became an eternal icon.

In every era, there are faces that not only define an aesthetic but embody an entire period. They are icons that defy time because they somehow managed to synthesize their deepest contradictions: beauty and pain, fame and loneliness, desire and disdain. In the 20th century, no face achieved this with as much power as Marilyn Monroe's. Her figure lives on, not just in black and white photos or Warhol's bright colors, but in the collective unconscious of a culture that turned her into both myth and merchandise.

Books, essays, biopics, and songs have been written about her. She has been mourned as a victim, idolized as a pop icon, and trivialized as a sex symbol. However, Monroe, more than any of these simplifications, was a woman who understood better than anyone the mechanisms of power, image, and desire in an industry that sold dreams at the expense of bodies. And though she died more than sixty years ago, her legacy remains more relevant than ever. Not out of nostalgia, but because her story anticipated, with brutal clarity, many of the discussions that public women face today.

She was born Norma Jeane Mortenson, a child passed between orphanages, foster families, and the burden of a sick mother. No one would have bet that this creature silenced by the system would become the most reproduced face of the 20th century, a woman with over 400 books written about her, an eternal icon of what glamour can hide. But Marilyn's story is not that of a puppet broken by fame; it is that of a puppeteer dressed in silk, a strategist with star makeup. Like a tragic heroine from great tales, Marilyn is more interesting when understood as an architect, not a victim.

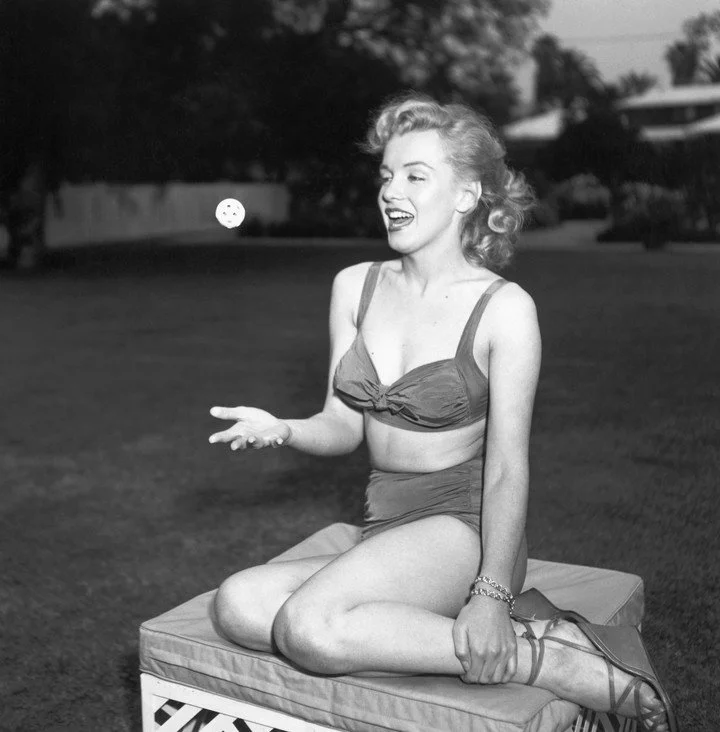

When World War II was still fresh in the memory of Americans, a young wife was working in a munitions factory in Van Nuys. There she was spotted by photographer David Conover, and that's when the myth began to build. With a transformation that seemed straight out of a pulp novel, Norma Jeane left behind her natural brown hair to become a platinum blonde, signed with 20th Century Fox, and began the meticulous creation of a character named Marilyn Monroe. This surname was not imposed on her: she chose it. She took it from her mother. Because Marilyn knew, even then, that you can't be someone without telling where you come from, even if you later have to rewrite everything to make it marketable.

Hollywood transformed her, but she also knew how to transform Hollywood. She understood that the studio needed a sex symbol, and she embodied that need with surgical precision, but not without control. She learned to pose, to move in front of the cameras, to exploit her angles as if she were drawing her own portrait. When the industry asked her to be sweet and docile, she laughed and gave them what they wanted, while silently weaving her own path. When she posed nude out of necessity, years before she was famous, she didn't deny it. On the contrary, she anticipated the scandal and explained: "I had debts. I'm not ashamed. I didn't do anything wrong." Instead of succumbing to public judgment, she reappropriated her body, her story, and her narrative. It was a masterful move. On the chessboard of scandal, Monroe always knew how to play her pieces.

Throughout her career, her intelligence was disguised as naiveté, her business acumen as charming clumsiness, and her defiance of female obedience norms mimicked the glow of flashbulbs. She was the "it girl" of 1952, the queen of the red carpet, the woman who made the whole planet watch movies just to see her laugh, sing, kiss, or cry. Her performance in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes left behind historic lines like, "I can be smart when occasion requires, but most men don't like it." A direct jab at the misogyny of an industry that underestimated her until the end. The scene of the white dress flying up in The Seven Year Itch not only defined an era, it defined the use of the body as a symbol of control. While everyone talked about how provocative the image was, Marilyn was talking to photographers, negotiating contracts, and planning her next move.

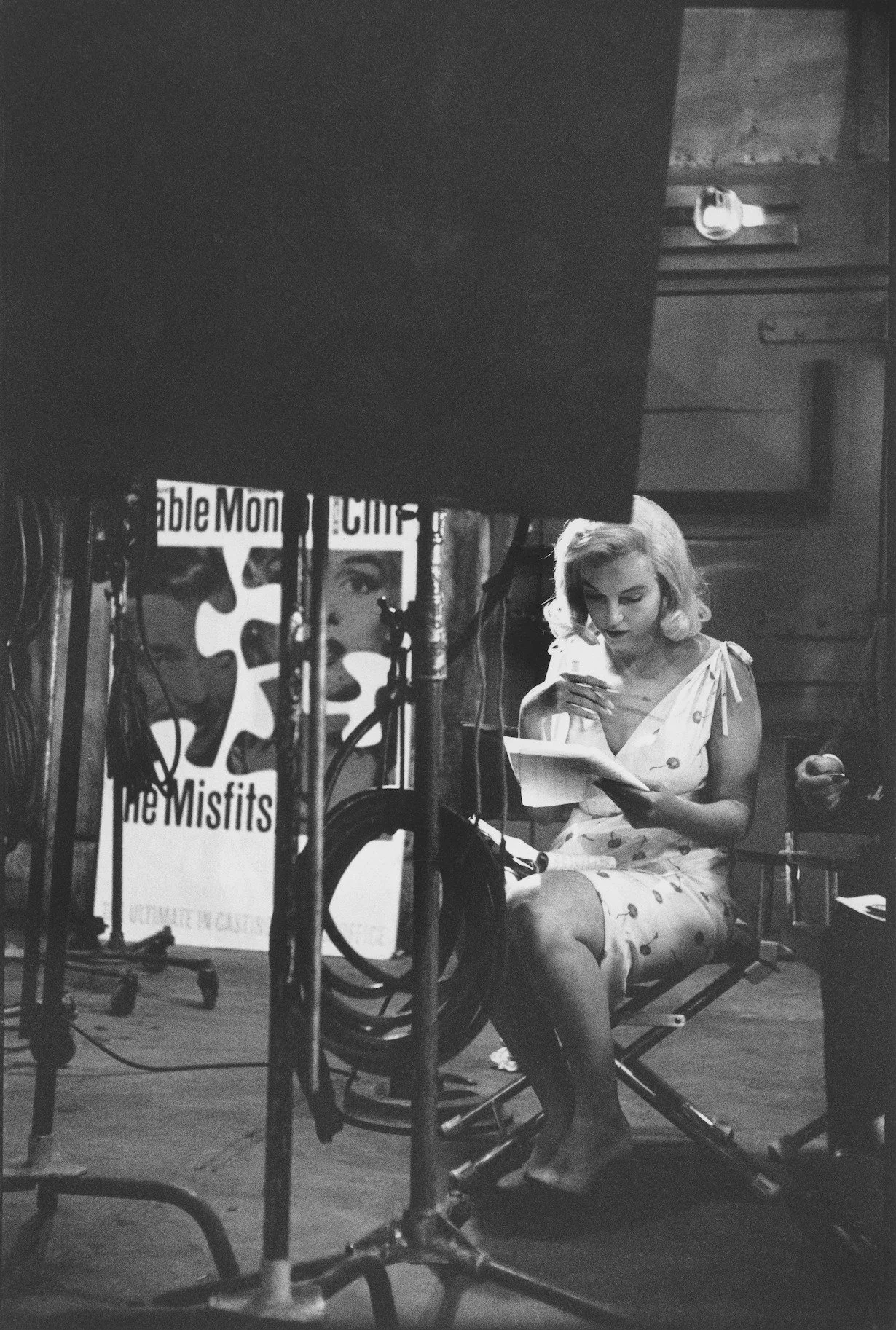

But being the most desired woman on the planet didn't save her from the glass ceiling. When she found out she was earning three times less than her male co-star, she walked off the set of The Girl in Pink Tights. She didn't ask for permission, she demanded respect. The studio suspended her but eventually caved. She returned stronger and with more control. She even founded her own production company, Marilyn Monroe Productions, at a time when women not only didn't run businesses but didn't even dream of doing so. It was this company that produced The Prince and the Showgirl, where she shared the screen with Laurence Olivier. An unprecedented act of audacity, as if she were saying: I don't need to be given a role, I'll write it myself.

She was also a pioneer in speaking about Hollywood's "wolves," predators who offered roles in exchange for sexual favors. In 1952, she wrote about them in the article "Wolves I Have Known," without names but with details. It was an early testimony of the #MeToo movement. She didn't do it out of public bravery, but with brutal clarity: she knew that intelligent denunciation was more powerful than screaming without a plan. Marilyn not only survived a system that devoured women, she understood it so deeply that she used it to her advantage.

Andy Warhol understood it like few others. His work Marilyn Diptych (1962), created shortly after her death, not only plays with the visual repetition of Marilyn's image, it plays with emptiness. With the idea that the image becomes hollow when reproduced infinitely. Marilyn was such a powerful symbol that she ended up split between the person and the character, between the broken woman and the immortal smile. Warhol captured that duality with chilling precision. And, unintentionally, he bore witness to what the "Marilyn Monroe syndrome" means: that state of being loved by everyone and known by no one.

Because Marilyn died alone. At just 36 years old, a barbiturate overdose closed her story. Officially, an accident. Unofficially, a lament. She had been battling insomnia, anxiety, and a deep sense of not belonging for years. Fame had turned her into a broken mirror in which everyone wanted to see themselves, but no one stopped to look at who was holding the glass. Dr. Elizabeth Macavoy, in her book The Marilyn Syndrome, described this ailment with a raw portrait: idolized people who end up emotionally empty, consumed by the distance between the myth and the skin.

However, it would be a monumental mistake to reduce Marilyn to her ending. It would be like defining a symphony by its last note. Because her legacy is one of light, reinvention, and defiance. She left an indelible mark on cinema: from The Asphalt Jungle and All About Eve to Some Like It Hot for which she won a Golden Globe as well as gems like Bus Stop and Niagara, Monroe consolidated a career that, despite its brevity, was as influential as that of any classic legend.

And beyond the movies, she changed the way of being famous. She understood everything before anyone else: the power of image, narrative, scandal as fuel. Today she would be an influencer, a CEO, perhaps a filmmaker. She would be a constant trend. But even in her time, she was disruptive. She was marketing in heels, feminism in slow motion, modernity dressed in sequins.

"Thank God we're all sexual creatures," she once said. And with that phrase, she disarmed the puritanism of an entire nation. She didn't say it with morbidity, but with truth. She didn't say it with arrogance, but with freedom. Marilyn Monroe was not a victim of Hollywood; she was one of its best strategists, a woman who knew when to be silent and when to explode. And who, like in the best classical tragedy, died knowing that she had already earned eternity.

Elton John called her Norma Jean and bid her farewell "like a candle in the wind." But Marilyn's flame remains lit. In every actress who demands fair pay. In every woman who decides her own image. In every voice that refuses to be silenced. Monroe not only defied the industry, she looked it in the eye, put on her makeup in front of its cruelest mirror, and decided yes: it was worth fighting. And in that fight, she became not just an icon, but a revolution wrapped in silk. A revolution that continues; centuries will pass and the world will not forget her because there will never be another like her.