HEROIN CHIC: THE STYLE THAT GLORIFIED THE POLITICALLY INCORRECT

A style, a trend, a reality. It was driven by fashion until it became a cultural icon. Today, the very industry that once glorified it is trying to erase it from its history.

The term "heroin chic" emerged in the 1990s as an aesthetic movement that quickly spread like a plague from fashion to film, music, and photography. At the time, it was a cry against the unattainable perfection that dominated the 1980s, with its sculpted bodies, golden skin, and chiseled features. The arrival of Kate Moss a petite teenager with pale skin, dark under-eye circles, and an extremely thin frame marked the beginning of a new visual era: disillusionment, fragility, and vulnerability turned into symbols of beauty.

The photo shoot titled "The Third Summer of Love", published by The Face magazine in 1990, was the starting point. With art direction by Phil Bicker, photography by Corinne Day, and styling by Melanie Ward, Moss perfectly embodied that aesthetic: a teenager who looked more like an orphan in a threadbare coat than a supermodel. It was the beginning of what became known as the waif look, which soon evolved into something much darker and more controversial: heroin chic.

In 1993, Kate Moss just 19 years old and with a budding modeling career crossed paths with Calvin Klein. At a time when 1980s fashion was marked by excess, the American designer sought to subvert beauty standards that celebrated curvy bodies and prominent breasts. Klein, who viewed surgically enhanced figures as offensive and unhealthy, chose Moss for his 'Obsession' perfume campaign. The black-and-white photographs, taken by Moss's then-boyfriend Mario Sorrenti, portrayed a makeup-free young woman with raw power and unprecedented naturalness. “There was no stylist. No one was doing my hair or makeup. It was raw, and it captured a moment in our lives,” Moss told Harper’s Bazaar. This unretouched campaign catapulted Moss to stardom and solidified her as the face of heroin chic, a trend that, unfortunately, led many women to suffer from anorexia and bulimia.

This new trend, far from presenting a healthy or aspirational image, seemed to openly celebrate addiction and physical deterioration. With skeletal bodies, hollow eyes, and vacant stares, models in this aesthetic didn’t hide their languid poses, which suggested endless nights of drugs and partying. What began as an aesthetic rebellion became a visual homage to decay. Fashion, in all its forms, immersed itself in that murky atmosphere. Magazines like Ray Gun and Surface, designers like Hedi Slimane, and photographers like Davide Sorrenti captured this world with unsettling realism, where extreme thinness was practically a requirement. Runways filled with ghostly figures like Jodie Kidd, Erin O’Connor, or Guinevere Van Seenus, whose appearances were celebrated and replicated to excess. In film, titles like Trainspotting, Pulp Fiction, Kids, and The Basketball Diaries reinforced the heroin imagery, while grunge music, led by Kurt Cobain, provided the soundtrack for this era of disillusionment and nihilism.

However, this fascination with a decadent aesthetic had very real consequences. The death of Davide Sorrenti in 1997, at just 20 years old, from a drug overdose, gave a traenti, publicly denounced the romanticization of addiction within the fashion world and called for urgent refogic face to a trend that until then had been celebrated for its “authenticity” or “rebellion.” His mother, Francesca Sorrrm. Gia Carangi, another key figure of heroin chic, also died as a result of her addiction. Her story was brought to the screen by HBO in 1998, with Angelina Jolie in the lead role, depicting the harsh reality of a life destroyed by drugs, despite the undeniable beauty that had once landed her on the cover of Vogue.

For some, like Surface’s creative director Riley John-Domel, the aesthetic represented a democratization of beauty ideals, moving away from the perfect bodies of Cindy Crawford or Elle Macpherson. For others, like designer Tom Ford, heroin chic was a way to convey attitude a portrayal of someone who had lived through it all. But this supposed sophistication soon showed its cracks. What appeared to be an artistic response to the superficiality of the 1980s became a cult of physical and emotional deterioration.

Photographer Corinne Day, responsible for many of the most iconic heroin chic images, said before her death that she never intended to glamorize suffering. The images she captured often starring Kate Moss reflected what she had lived in her youth: young people without a future, miserable surroundings, messy rooms, and vulnerable bodies. Her work, far from the cleanliness of traditional fashion editorials, forced the viewer to look at what is usually hidden. Yet over time, the grotesque was consumed by the industry and turned into a commodity.

Hedi Slimane, another major figure of the style, took this aesthetic to its limits in his collections for Saint Laurent Paris. He not only designed but also photographed. His love for music and obsession with youth led him to immortalize figures like Courtney Love or Daft Punk, blending punk attitude with the sophistication of luxury fashion. In his black-and-white images, models appeared to float between the high of a live show and the crash afterward, reinforcing the narrative of a world that was beautiful but broken.

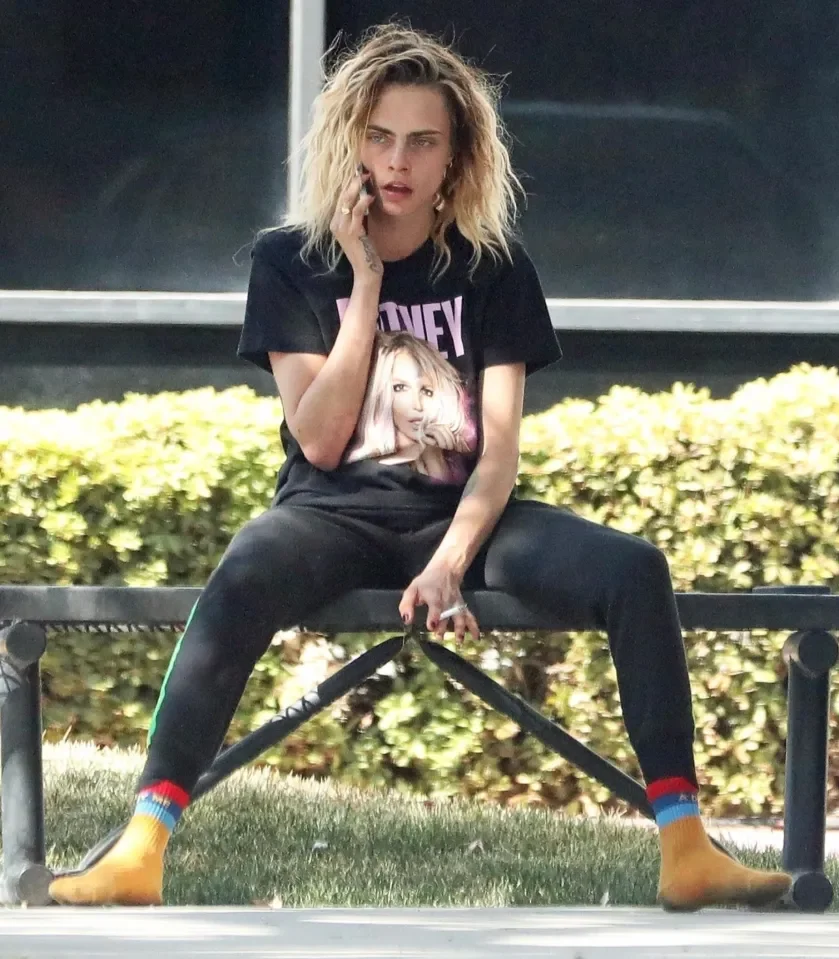

Beyond the 1990s, the shadow of heroin chic hasn’t completely vanished. New figures like Kristen Stewart or Mary-Kate Olsen have flirted with this aesthetic. Sasha Pivovarova, with her sickly appearance and sharp cheekbones, embodied the 2000s revival. On social media, the cult of extreme thinness continues disguised as trends or lifestyle. Though platforms like TikTok and Instagram have banned terms such as "heroin chic" or "thinspo", this hasn’t stopped such content from migrating to other digital spaces.

In this context, the discussion has resurfaced strongly, driven by a new factor: Ozempic. This injectable diabetes medication, launched in 2017 with the active ingredient semaglutide, went viral on social media about two years ago. Influencers shared stories of rapid weight loss, bringing the hashtag #ozempic to millions of views on TikTok and Instagram. Celebrities like Oprah Winfrey, Stephen Fry, Kelly Clarkson, and Elon Musk have admitted to using it, normalizing its use not just for obesity or diabetes, but also for those simply seeking fast weight loss. Ozempic’s growing popularity is further fueled by the strong return of Y2K culture a trend that embodies early-2000s fashion nostalgia, with its low-rise jeans and miniskirts, reviving the obsession with extreme thinness that defined the heroin chic era.

The drug’s omnipresence has even led to shortages for diabetic patients who genuinely need it. Novo Nordisk, the Danish pharmaceutical giant that produces Ozempic and Wegovy (another semaglutide drug approved specifically for weight control), is now the most valuable company in Europe. The controversy surrounding drug-induced thinness became clear at Berlin Fashion Week, when the brand Namilia showcased a shirt reading "I Love Ozempic," sparking strong backlash for its “toxic” and “superficial” message. While Namilia clarified that the shirt was intended as an ironic commentary on fame’s pressures and unrealistic body ideals, German-Turkish model Khan, who walked for the brand, interpreted the message as a critique of the return of heroin chic.

Khan, one of the few plus-size models in the industry, senses the return of the size-zero ideal. “I was often confirmed for jobs and then dropped after comparison with the stylist because of my size,” she told DW. Her observations are supported by Vogue Business' latest report, which revealed that in the Fall/Winter 2024 season, less than 1% of models on the runways of New York, London, Milan, and Paris were plus-size. This suggests a return to preferences akin to those of designers like Karl Lagerfeld, infamous for his fatphobic remarks.

An article in the New York Post even proclaimed the return of the trend with the provocative headline: “Bye-bye booty: Heroin style is back.” The backlash was swift. Celebrities like Jameela Jamil condemned the trivialization of the human body as a passing trend. “Our bodies are not trends,” she wrote, while Emma Specter, writing for Vogue, rejected the idea that new generations should once again be subjected to the destructive standards of the 1990s.

The problem, critics say, is that this is not just an aesthetic it’s an entire value system that glorifies suffering, fragility, and exclusion under the guise of rebellion. Writer and former editor Atoosa Rubenstein recalled how even Jennifer Aniston was once deemed “too fat” to be on a cover. The pressure was so great that even magazines that aimed to diversify body representation, like Seventeen or CosmoGirl, often relegated such inclusion to special issues. Today, although social media has democratized beauty standards and voices, many worry that brands are using body positivity as a marketing façade. As Rob Smith, founder of inclusive brand Phluid Project, explains, clothing design still centers on small sizes, and inclusion is often a strategy not a structural shift.

At a time when mental health and body dysmorphia are central to public debate, it is especially irresponsible to revive uncritically terms like heroin chic. The phrase carries not just a visual style it bears the weight of premature deaths, devastating addictions, and a system that glorified suffering as authenticity for far too long. The fascination with darkness, visual drama, and what remains unsaid in images can be understood from an artistic point of view, but the trivialization of physical and mental decline no longer has a place.

The legacy of heroin chic if it can be called that should serve as a warning, not an inspiration. The images that once captivated the world with their rawness and honesty should remind us that behind every model with sunken eyes or black-and-white shoot, there was often a broken life, an exhausted body, and an industry willing to look the other way. As photographer Nan Goldin, whose work also depicted heroin use through raw and unglamorous experience, once said: “They are what you see; nothing more.” And what we see today should compel us to look beyond the pose.