THE BEST CHRISTMAS MOVIES TO WATCH THIS SEASON: CLASSICS THAT DEFINE THE HOLIDAYS

Get ready for a season of warmth and emotion. These are the films that return every Christmas to keep us company and reconnect us with the spirit of the season.

This season, watching these Christmas films is a small ritual. A hot coffee with a warm croissant, a shared pizza, blankets on the couch, chocolate chip cookies still soft. Christmas cinema asks for nothing more. Just being there, letting yourself be wrapped up, and allowing the world if only for a momento to feel kinder, slower, more human.

These stories don’t function only as entertainment, but as companionship. They accompany cold days and long nights, when the lights dim and the home becomes a refuge. From the physical, heartfelt comedy of Home Alone to the ensemble romance of Love Actually; from the expansive innocence of Elf to the acidic humor of Bad Santa, each title proposes a different way of experiencing Christmas.

There is room for nostalgia, exaggerated laughter, and restrained emotion. The Holiday invites us to imagine another possible life; The Polar Express reminds us that believing is also a choice; The Santa Clause, Jingle All the Way, and Last Christmas transform chaos, love, and loss into intimate stories.

Returning to these classics is accepting that Christmas doesn’t need perfection. A story, something warm in your hands, and the desire to stay is enough. There may be no better plan.

HOME ALONE (1990)

When Home Alone arrived in theaters in 1990, it seemed like just another Christmas comedy. It quickly became a global phenomenon. Directed by Chris Columbus and written by John Hughes, the film grossed over $475 million worldwide, becoming one of the most successful comedies in history and redefining the commercial potential of family cinema.

The plot is simple and effective: Kevin McCallister, a boy accidentally left home alone during Christmas vacation, discovers both the freedom and danger of solitude. The film blends physical comedy, visual wit, and precise pacing, especially in the confrontations with the bumbling burglars played by Joe Pesci and Daniel Stern.

But its impact goes beyond comedy. Home Alone connects with universal themes such as loneliness, the desire to belong, and the importance of family. Macaulay Culkin’s charismatic and emotionally precise performance anchors a film that, decades later, remains an essential Christmas classic.

HOME ALONE 2: LOST IN NEW YORK (1992)

Released in 1992, Home Alone 2: Lost in New York took the formula of the original success and amplified it with urban ambition and spectacle. Directed once again by Chris Columbus and written by John Hughes, the sequel was a commercial triumph, grossing over $350 million worldwide and confirming Kevin McCallister as a Christmas movie icon.

This time, Kevin doesn’t stay home alone but accidentally lands in New York City, filmed as both playground and danger zone. The Plaza Hotel, toy store windows, and Central Park become extensions of his imagination. The return of the “Wet Bandits” pushes the physical comedy into near-cartoon territory more exaggerated, but just as effective.

Though less intimate than the first film, it retains its emotional core. Home Alone 2 celebrates childhood independence, the spirit of the city, and the magic of Christmas, securing its place as a loud, endearing, and essential holiday sequel of the 1990s.

HOW THE GRINCH STOLE CHRISTMAS (2000)

High atop a snowy mountain lives a creature who despises Christmas, though in truth he fears the community that celebrates it. Directed by Ron Howard, How the Grinch Stole Christmas adapts the world of Dr. Seuss with an exaggerated aesthetic fully aware of its own artifice, where satire coexists with a classic moral fable. Whoville appears as a riot of color and exaggerated gestures, reflecting a celebration trapped in excess and consumerism.

Jim Carrey delivers a physical, elastic performance that turns the Grinch into a corrosive yet vulnerable character capable of carrying the film even at its noisiest moments. Beneath the hyperbolic humor lies a simple, effective idea: Christmas doesn’t live in objects, but in human connection.

Makeup was essential to the film’s visual construction. Every extra and character required several hours of daily prosthetics to achieve unique, caricatured features, while Carrey himself spent up to three hours in makeup making visual design a core part of the storytelling.

THE SANTA CLAUSE (1994)

One accidental night is enough to transform a family comedy into a light reflection on identity and responsibility. The Santa Clause presents an improbable premise a divorced father who, after a Christmas Eve accident, is forced to become Santa Claus and develops it with a tone that balances adult irony and childlike fantasy. Tim Allen, in one of the most defining roles of his career, brings an earthly skepticism that makes the transformation from ordinary man to mythical figure believable.

The film’s strength lies in small details: North Pole bureaucracy, adult disbelief, and the gaze of a child who needs to believe. More than a Christmas fable, it’s a story about accepting an unexpected role and learning how to inhabit it.

Visually restrained yet effective, the film relies on concept over excess. To bring Allen’s transformation to life, the makeup team used progressive prosthetics applied daily, allowing the character to age and physically expand throughout the shoot reinforcing the idea of inevitable metamorphosis.

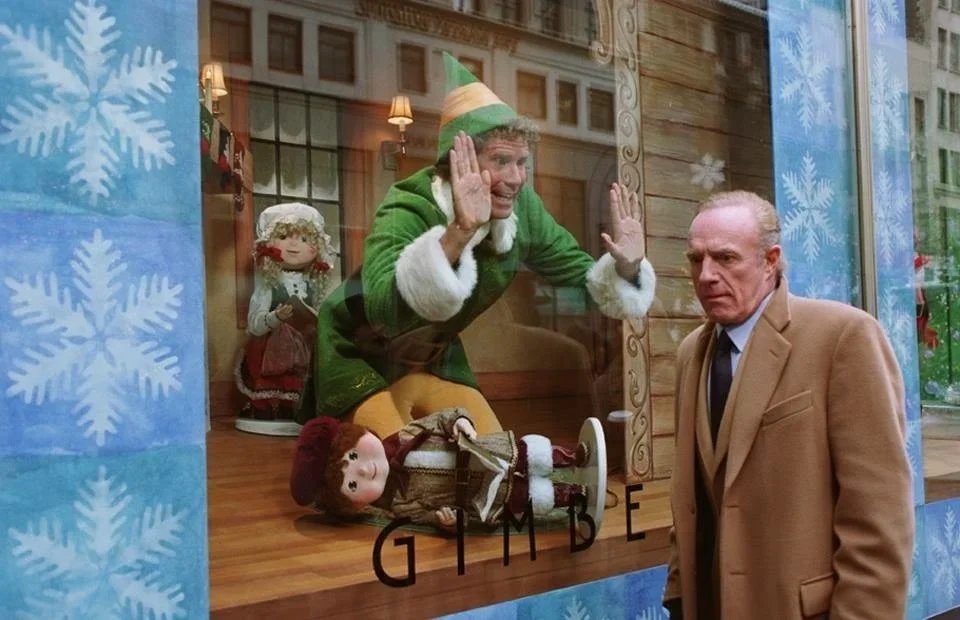

ELF (2003)

Elf approaches Christmas through the confusion of an outsider. Buddy, a human raised by elves at the North Pole, arrives in New York with a childlike faith that collides head-on with urban cynicism. Directed by Jon Favreau, the film finds its tone in that contrast: absolute innocence versus a city that has forgotten how to believe. Will Ferrell delivers a physical, disarming performance more vulnerable than bombastic that turns Buddy into more than an extended joke.

The film moves with classic comedy pacing while allowing moments of unexpected tenderness. It doesn’t mock innocence; it defends it. Beneath the visual humor and obvious gags, Elf proposes a simple but effective idea: joy can be an act of resistance.

Visually, the film embraces a deliberately handmade aesthetic. Many North Pole scenes were shot using forced perspective techniques inspired by Rankin/Bass Christmas specials, making Buddy appear gigantic next to the elves without heavy reliance on digital effects.

LOVE ACTUALLY (2003)

Love Actually intertwines stories as if Christmas were merely an excuse to observe love in all its forms: romantic, awkward, unrequited, mature, or silent. Directed by Richard Curtis, the film unfolds as an emotional mosaic that oscillates between lightness and melancholy, aware that love is rarely grand without also being uncomfortable. Set in a London pulsing with carols and airport farewells, the film favors small gestures over grand declarations.

Its ensemble cast yields uneven moments, but also genuine intimacy that withstands time. More than a conventional romantic comedy, Love Actually functions as an inventory of imperfect emotions, where happiness is never absolute and loss coexists with hope.

The film became a defining reference of modern Christmas cinema and cemented Heathrow Airport as a symbolic space of everyday love so much so that several scenes were shot with hidden cameras among real passengers to capture authentic reunions.

THE POLAR EXPRESS (2004)

The Polar Express proposes a Christmas shaped by doubt. Directed by Robert Zemeckis, the film follows a boy who boards a train to the North Pole on Christmas Eve, embarking on a journey that tests his capacity to believe. Far from easy sentimentality, the film adopts a contemplative, almost unsettling tone, where wonder coexists with a sense of unease.

The motion-capture animation seeks an unusual human fidelity for its time, creating a visual universe that oscillates between the real and the spectral. This ambiguity reinforces the central theme: childlike faith is not naivety, but a conscious choice in the face of skepticism. Tom Hanks, performing multiple roles, provides emotional continuity to a story that unfolds like a modern fable.

More than a Christmas adventure, The Polar Express is a meditation on the passage from childhood to maturity. During production, actors were filmed wearing more than 300 body and facial sensors a pioneering process that marked a turning point in early 21st-century digital animation.

THE HOLIDAY (2006)

The Holiday finds its charm in calculated escapism. Two women, separated by an ocean and united by romantic disappointment, swap homes during the holiday season and discover almost despite themselves new versions of who they are. Directed by Nancy Meyers, the film moves with her signature elegance: luminous interiors, sharp dialogue, and a romanticism that never apologizes for itself.

Cameron Diaz and Kate Winslet offer complementary performances, while Jude Law and Jack Black serve as unexpected counterpoints. More than a traditional romantic comedy, The Holiday is an adult fantasy about emotional reset, where love appears not as destiny, but as the result of learning to listen to oneself.

The film turns its settings the English cottage and the California home into silent characters reflecting opposing states of mind. To achieve that idealized atmosphere, several scenes in the idyllic English village were filmed on purpose-built sets, as the real location lacked the “perfect” aesthetic the script required.

JINGLE ALL THE WAY (1996)

Jingle All the Way approaches Christmas through the chaos of consumerism and parental guilt. Arnold Schwarzenegger plays an absent father who, in a last-ditch effort at redemption, embarks on a desperate race to secure the season’s most coveted toy. The film turns this premise into a loud satire of holiday commercial obsession, where good intentions often arrive too late.

Directed by Brian Levant, the film relies on the contrast between Schwarzenegger’s imposing physicality and a domestic environment that emotionally overwhelms him. The humor is broad and exaggerated, yet points to a recognizable truth: Christmas can become an absurd competition when measured in objects. Beneath the physical comedy lies a critique of family stress and social pressure to “deliver.”

Over time, Jingle All the Way has achieved ironic classic status. The story was inspired by real events from the 1990s toy craze, when products like Tickle Me Elmo sparked chaotic shopping scenes similar to those depicted in the film.

BAD SANTA (2003)

Bad Santa dismantles the Christmas myth with an unusual bluntness for a studio comedy. Billy Bob Thornton plays Willie, an alcoholic, cynical, and morally exhausted Santa Claus who uses his seasonal job to rob shopping malls. Directed by Terry Zwigoff, the film advances with dark humor and calculated discomfort, refusing to soften its protagonist or redeem him easily.

The film’s strength lies in the contrast between Christmas’s childlike iconography and the adult desperation that runs beneath it. Thornton delivers a restrained, bitter performance more sad than provocative that avoids caricature even at its most excessive. Beneath the sarcasm and political incorrectness, Bad Santa poses an uncomfortable question: what remains of the Christmas spirit once all illusion is gone?

Rejecting sentimentality, the film embraces brutal honesty that turned it into a cult classic. During production, two versions of several scenes were filmed one explicit and one softened to ensure theatrical release without sacrificing the film’s corrosive tone.

LAST CHRISTMAS (2019)

Last Christmas wraps melancholy in festive lights. Set in a wintery London, the film follows Kate, a young woman trapped in a cycle of poor decisions and personal disappointment, who finds an unexpected sense of balance after meeting a man as enigmatic as he is optimistic. Directed by Paul Feig and written by Emma Thompson and Bryony Kimmings, the film oscillates between romantic comedy and emotional drama, with a more reflective tone than its premise suggests.

Emilia Clarke portrays a fragile, erratic protagonist far from the traditional romantic ideal, while George Michael’s music infuses the story with nostalgia and longing. The film moves lightly but holds a twist that reframes its sentimentality, ultimately favoring empathy and redemption.

More than a conventional love story, Last Christmas reflects on second chances and gratitude. The script was conceived around George Michael’s lyrics and songs, which he had approved before his passing making the music both a narrative and emotional axis of the film.

In the end, Christmas cinema is not about plots or memorable twists, but about atmospheres. About that almost invisible feeling that settles in when the screen lights up the room and the outside noise fades away. These films function as emotional shelters: they don’t promise revelations, but they do offer the certainty of a shared momento even in solitude.

Returning to them is a conscious gesture. It’s choosing warmth over haste, familiarity over the constant saturation of novelty. Every laugh, every predictable scene, every known ending brings something reassuring: the idea that not everything needs to surprise in order to matter.

This season, letting yourself be carried by these classics is a form of care. A simple way to reconnect with what’s essential, to allow time to stretch, and to let Christmas feel not like an obligation, but like a pause. The movies do the rest.